Common Data Formats

In this previous section, we defined “raw” data as the data we begin with. “Raw,” in other words, is a relative term. The raw data in our example was in the form of a plain text file minimally structured using the CSV file format. Some data has even less structure than this. It may come to us in the form of jottings in a notebook, for example, or audio recordings. As already mentioned, “raw” data may be produced by our own observations or shared with us by someone else who has done the initial collection and who may have done some additional processing before making it available.

If we’ve done the data collection ourselves, we may have recorded it in a spreadsheet with an eye towards analyzing it later, and perhaps even with ideas about the kind of analysis we’d like to do.

However, data shared with us isn’t likely to come in the form of a spreadsheet. An Excel file, for example, will be large if it contains a lot of data, making it unwieldy to store or download. If it contains anything other than simple data—for example, if it contains cells with formulas—it may not be readily usable by other tools for analysis, such as Python and R.

We’re more likely to find shared data in CSV or some other plain text format. In addition to CSV, two formats that we’ll briefly examine here are XML (short for eXtensible Markup Language) and JSON (JavaScript Object Notation). Both provide more structure than CSV.

CSV

As the name “Comma Separated Values” denotes, and as we’ve already seen, this format uses commas as a “separator” between values. Each new line of a CSV file is the equivalent of a row in a spreadsheet. Let’s say our data set contains cat names. It might look something like this:

First Name,Last Name

Smally,McTiny

Kitty,Kitty

Foots,Smith

Tiger,Jaws

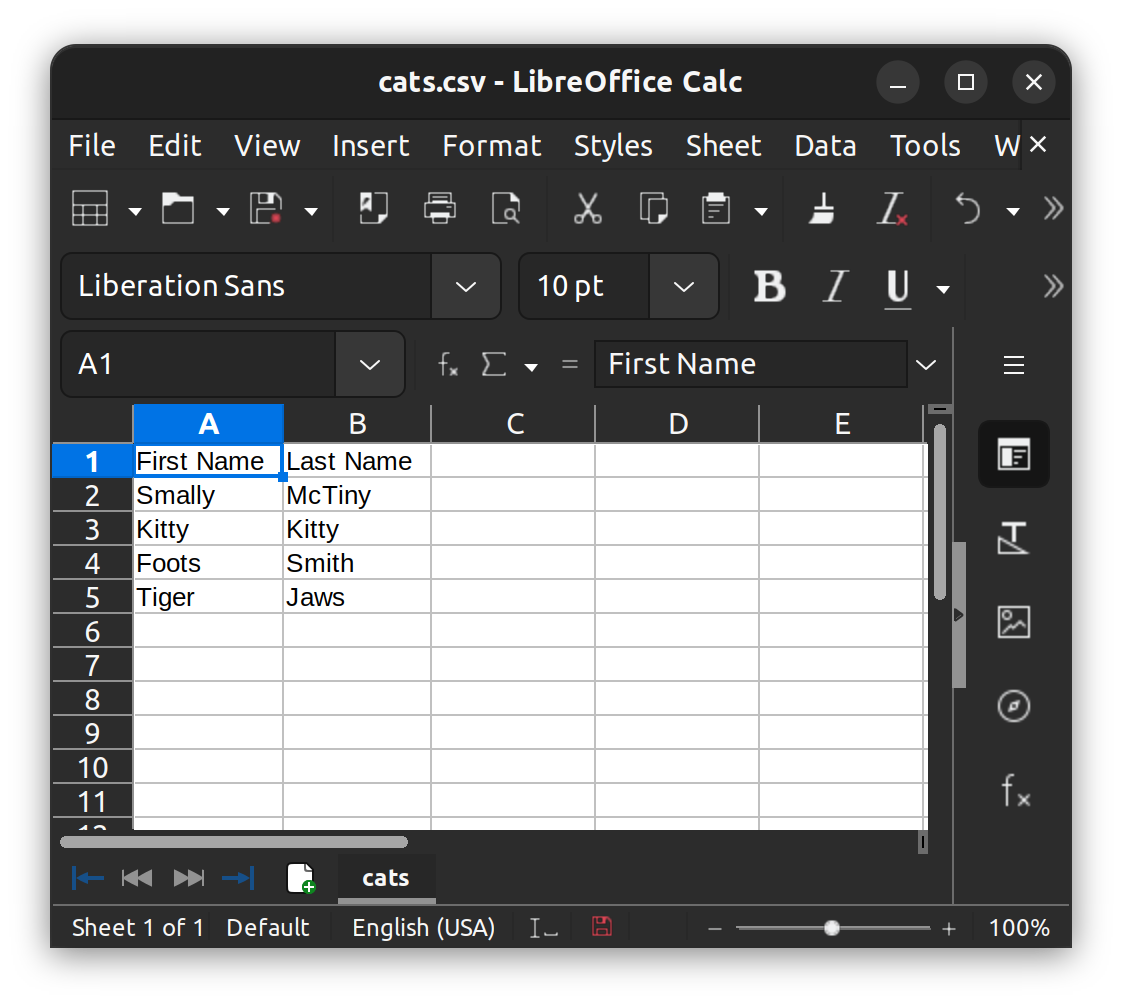

Notice that the commas don’t have to align from one row to the next as column lines do in a spreadsheet. Notice also that there’s no punctuation at the end of each line; the line-end marks the end of the row. If we opened this file in a spreadsheet, each line would become a row. The first row would contain our column headings, and subsequent rows would contain first and last names of cats. It would look something like this:

If commas are being used by the CSV format to separate values, what happens if one of our values contains one or more commas? Let’s imagine a different data set, one with names and (somewhat fanciful) addresses:

Name, Address

Smally McTiny, "Mom's bedroom, upstairs"

Kitty Kitty, "Jessie's house, next door"

Foots Smith, "Sal's house, across the street"

Tiger Jaws, My room

To prevent the commas in the first three addresses from being interpreted as separators, we enclose each entire address value in quotation marks. We can omit the quotation marks for the fourth address, although no harm would come from using them there as well.

Another approach we could take is to use \ as an escape character before the non-separator commas, marking them as not to be understood as separators, thus:

Name, Address

Smally McTiny, Mom's bedroom\, upstairs

Kitty Kitty, Jessie's house\, next door

Foots Smith, Sal's house\, across the street

Tiger Jaws, My room

Most spreadsheet programs will open .csv files and ask you to confirm that you’d like the program to recognize commas as your value separators. (Other separators are possible for storing minimally structured values in plain text. Another common separator is the tab character. Tab-separated values files usually use the extension .tsv in their names. Broadly, they operate just the way comma-separated values files do, with tab playing the role that commas do in .csv files.)

XML

XML is a markup language. You’ve already encountered HTML (HyperText Markup Language) and its simplified derivative Markdown. Like HTML, XML encloses text and number data within elements. Unlike HTML, XML gives you, as the creator of a file, nearly unlimited freedom to name and define elements and attributes to suit your purpose. This is what makes the language “extensible.”

XML element and attribute definitions are stored in a separate file, such as a DTD (Document Type Definition) or a file written in a schema language such as XML schema.

Like HTML, XML has a nested or tree-like structure. In XML, our cats data might look like this:

<Cats>

<Cat>

<firstName>Smally</firstName>

<lastName>McTiny</lastName>

</Cat>

<Cat>

<firstName>Kitty</firstName>

<lastName>Kitty</lastName>

</Cat>

<Cat>

<firstName>Foots</firstName>

<lastName>Smith</lastName>

</Cat>

<Cat>

<firstName>Tiger</firstName>

<lastName>Jaws</lastName>

</Cat>

</Cats>

In this representation, the <Cats> element encloses a list of cats, and the <Cat> element encloses the first and last name of each cat in our cat data set. For each cat inside a <Cat> element, the <firstName> element encloses the cat’s first name, and the <lastName> element encloses its last name.

JSON

Like XML data, JSON data has nested structure. In the example below, "Cats": introduces a list of cats. The entire list is enclosed in square brackets ([]), and the data entry for each cat is enclosed in curly brackets ({}). Each entry consists of a key:value pair, and each such pair within an entry is separated by a comma.

{

"Cats": [

{

"firstName": "Smally",

"lastName": "McTiny"

},

{

"firstName": "Kitty",

"lastName": "Kitty"

},

{

"firstName": "Foots",

"lastName":"Smith"

},

{

"firstName": "Tiger",

"lastName":"Jaws"

}

]

}

A JSON file will display in a browser in a way that makes it easy to collapse and expand the nested contents. You can test this yourself by copying the JSON data above, saving it to a file named cats.json, and opening the file in the browser of your choice.