One Text, Three Views

As previously mentioned, plain text is a highly interoperable format for storing and sharing textual content (e.g., books, blog posts). We can work with plain text documents in any text editor or even in a terminal window. We can begin working on a plain text document with one of these tools, save it, then open it in another and pick up right where we left off. The visual presentation of the text content may vary from one tool to another (for example, by including syntax highlighting), but the content itself will not.

Let’s test this out for ourselves.

Project Gutenberg makes public domain works of all kinds available in multiple formats, including plain text. Open a browser and direct it to

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/205/205-0.txt

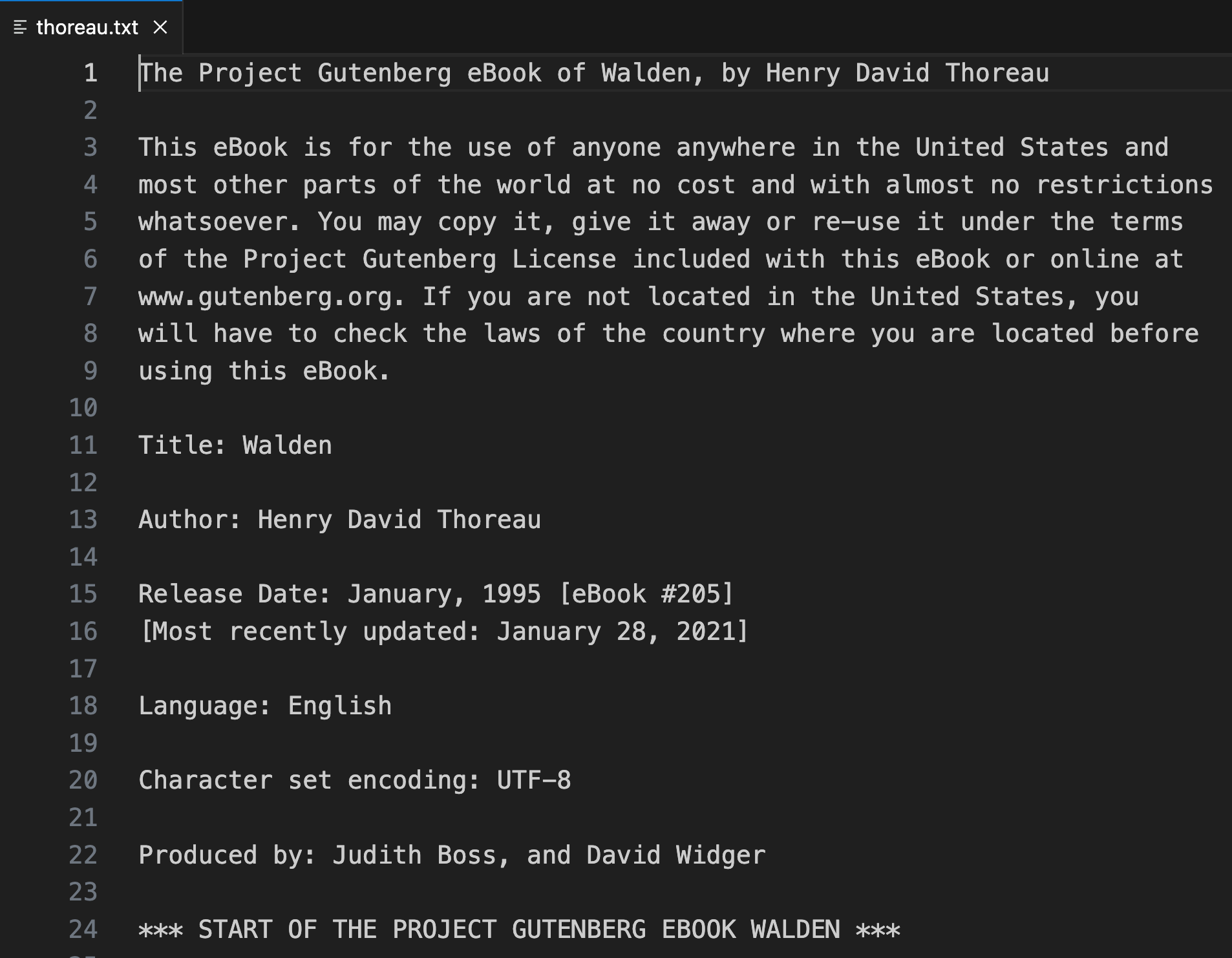

Your browser will show you a plain text version of Walden and Civil Disobedience, by Henry David Thoreau. It should look something like this.

Let’s pause a moment to notice a couple of interesting things here. Three lines from the bottom of the above screenshot, you’re seeing information about the encoding standard that this plain text file is using. It’s a different standard from the one we used in the previous section, ASCII. The Gutenberg file is encoded using the UTF-8 encoding scheme, which is part of the Unicode standard. Unicode, first introduced in 1991, was developed to address significant limitations in ASCII, which, among other limitations, lacks the capability to represent the variety of the world’s languages. Unicode provides not only comprehensive support for text characters across languages but support for a wealth of symbols, including emoji. 🙂

Notice also, a few lines above, the release date for this copy of Walden: 1995. Plain text doesn’t only hold up well across operating systems and software applications; it also holds up extremely well over time.

Now open a terminal window and type (or paste)

curl https://www.gutenberg.org/files/205/205-0.txt | less

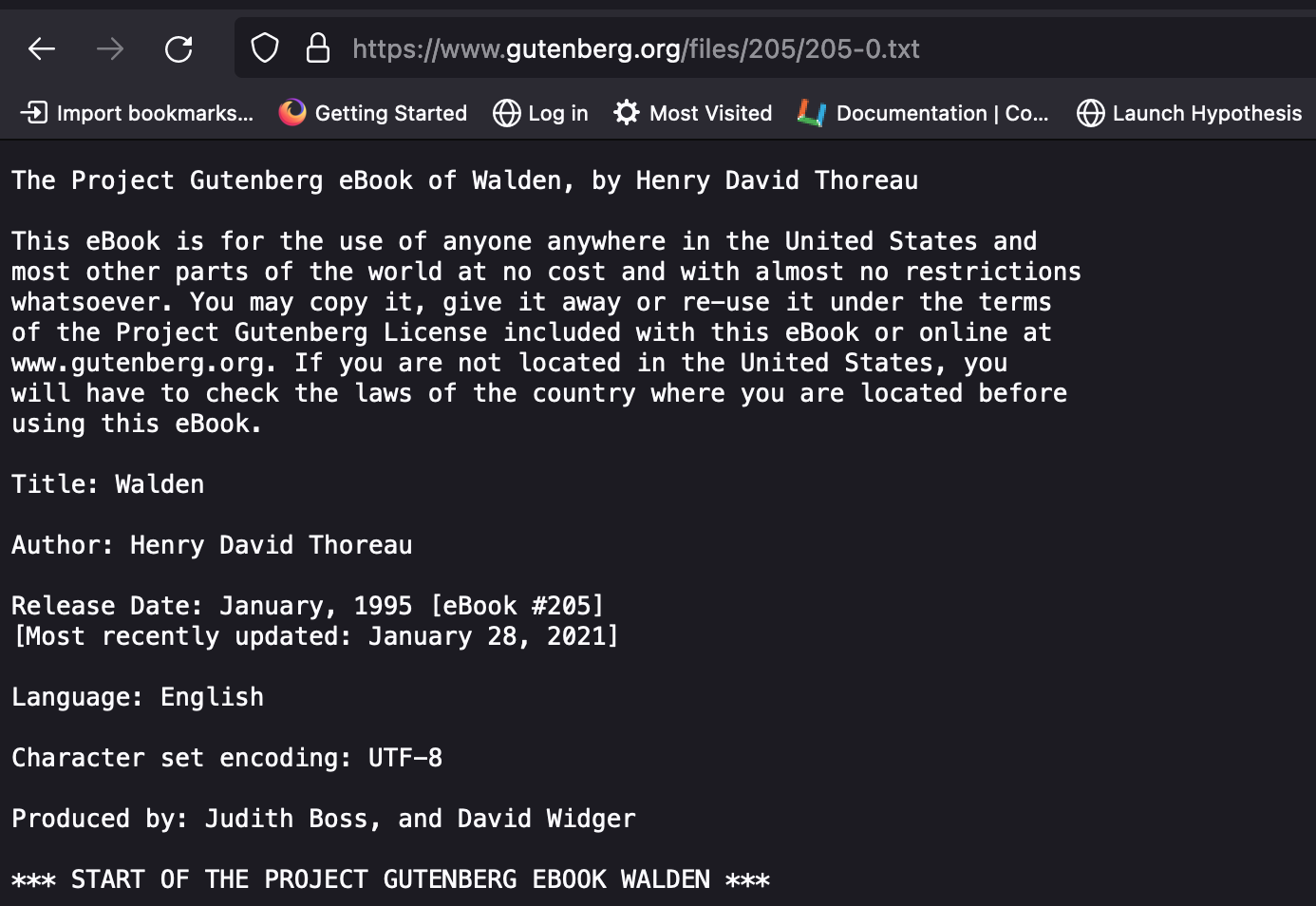

You may have to wait a few seconds, but very soon you should see exactly the same content in your terminal window that you see in your browser. What happened here? You used the curl command to get the contents of the file from Project Gutenberg, then you piped the output of that command to less, which shows you the first page of the contents. (On a Mac, you can move up and down in the file one page at a time by holding down the fn key and using the up/down keys; in Windows, you can use the PgUp and PgDown keys.)

Whether you’re in your browser or your terminal, you’re looking at a file that’s been transferred from a remote computer to your own. The remote computer is one capable of serving files to other computers that connect to it—hence the term server. The server hosts the file, accepts connections from client computers like your own, and responds to a request for the file—such as that made by your browser or by curl—by delivering the file’s contents.

In either case, the file’s contents are printed to your screen, but they’re not permanently saved anywhere on your computer’s own drive; they’re saved only temporarily in your computer’s memory. With curl, you can take the next step and save those contents locally by adding a redirect. Let’s try this out.

To get out of Walden in your terminal, type q. That will land you back at the command prompt.

Now, navigate to your home folder:

cd ~

Next, make a directory to store the file you’re going to download, and move into that directory. (In the example below, it’s named thoreau-folder. Use any name you like, but remember: no spaces!):

mkdir thoreau-folder

cd thoreau-folder

Take a peek inside:

ls

The ls command should return no output because you haven’t yet put any files in this new directory. If you do see output—files and/or folders—you’re in the wrong place. Type

pwd

figure out where you are, and try again!

Once you’ve created a folder to hold your plain text copy of Walden and moved into it, type (or paste)

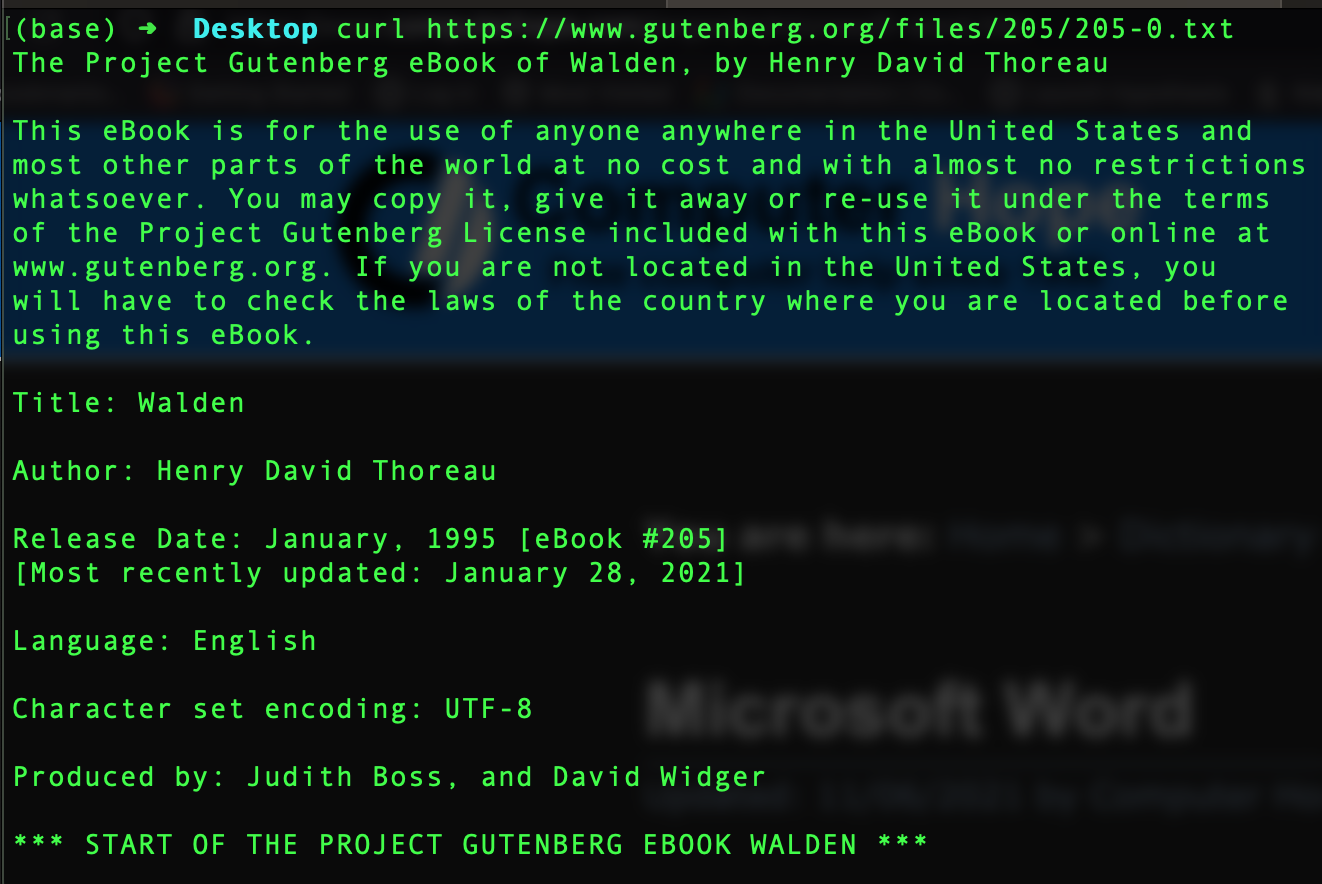

curl https://www.gutenberg.org/files/205/205-0.txt > thoreau.txt

The file will be saved in the folder you created. If you switch over to your Finder or File Explorer and navigate to that folder, you should see a new file there, thoreau.txt. (If you’re running Ubuntu for Windows, this will be the home folder of your Linux installation, not your Windows home folder.)

You can right-click on it and tell your computer to open it in VS Code. Or, from the command line, you can type:

code thoreau.txt

The file will open in VS Code, where it should look pretty much the same as it does in both your terminal window or your browser.

That’s the interoperability of plain text!