Teaching Jackie Robinson during the covid pandemic

20 Mar 2021

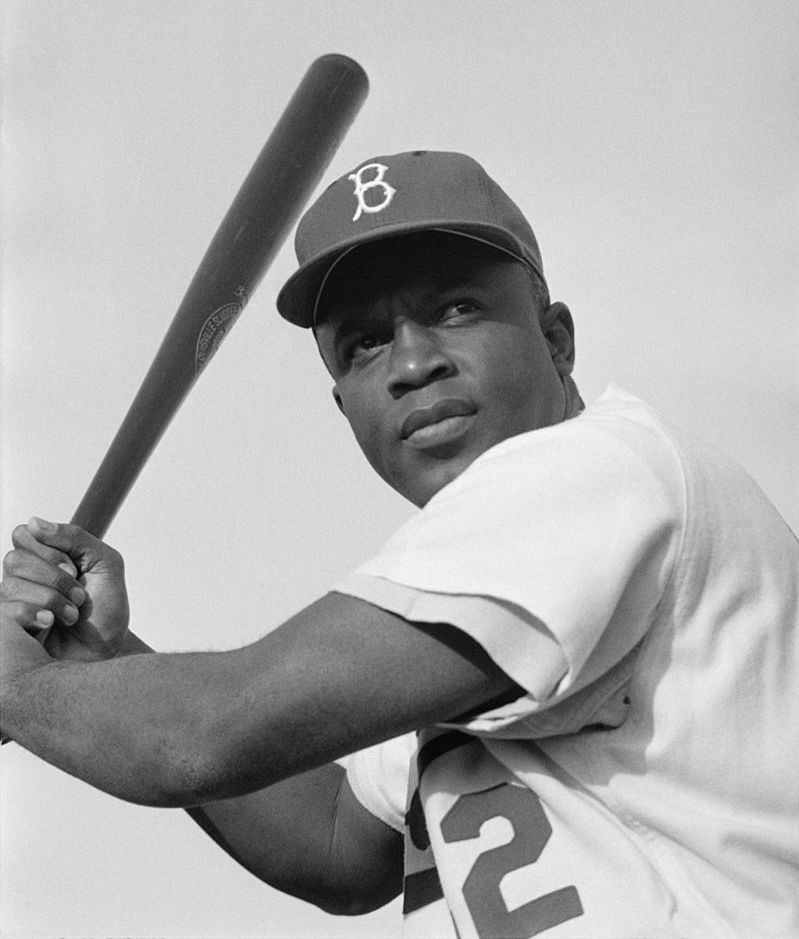

Jackie Robinson, Brooklyn Dodgers, 1954. Photo by Bob Sandberg, Look photographer. Restoration by Adam Cuerden. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Jackie Robinson, Brooklyn Dodgers, 1954. Photo by Bob Sandberg, Look photographer. Restoration by Adam Cuerden. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Editor’s note: During the January 2021 Intersession, as part of Geneseo’s project of becoming an antiracist college, nearly a dozen faculty taught courses that either focused centrally on issues of racial justice or incorporated those issues via dedicated modules and interwoven content. Professor Behrend’s post is one in a series in which faculty reflect on their objectives and experience in these courses. You can read previous posts in this series by Professor Melanie Medeiros and Professor Meredith Harrigan.

For as long as I can remember, I have been a baseball fan. And not just a baseball fan, but a Dodger fan. Watching Dodger games on television and attending games at Dodger Stadium was a memorable part of my upbringing in Los Angeles.

I don’t remember when I first learned about Jackie Robinson. He is, of course, known for breaking the color line in baseball: the first Black ballplayer in the major leagues in the twentieth century. But he’s also a Dodger legend. So I’ve long taken pride that my team — the Dodgers — was the team that began to break down segregation in baseball.

As I grew older and became a historian, specializing in the history of African Americans, I still maintained my love of Dodger baseball, but I kept it in a separate realm. I was a fan. I enjoyed baseball; I didn’t study it. But then the pandemic began, almost one year ago now, and it disrupted practices and assumptions. Like many people, I struggled with the lockdown and grew frustrated with the hours of isolation from friends, extended family, and public spaces.

Baseball, however, provided some solace. I watched baseball on TV as the MLB attempted an unprecedented and abbreviated schedule that included less than half the regularly scheduled games and new protocols to limit the spread of Covid-19. Despite the unusual season, it all turned out well for my Dodgers. They won the 2020 World Series and provided me with a wonderful diversion from the harshness of pandemic life.

An idea for a course

As the Dodgers were making their way through the playoffs in early October, I began to think that a course on sports might make for an interesting intersession offering. I had never taught an intersession course before. I had never taught a fully online course before, and I also had not taught sports history. Then again, I had never experienced a lockdown before, used Zoom, or worn a face mask in public. Things were changing. For such a short period of time — four weeks — I thought that a course built around one person might provide a workable structure, and I could think of no one better to focus on than Jackie Robinson.

I had a general understanding of Robinson when I proposed the course, but as I read more I realized that I could use his life (1919-1972) as a framework to understand the history of American racism in the twentieth century. He was born in the Jim Crow South, like most African Americans before 1915. His mother fled sharecropping in Georgia to settle in Pasadena, California, much like millions of other Black people who moved to northern and western cities during the Great Migration. After college, Robinson enlisted in the army during World War II and challenged the segregated military. After the war, in 1947, he broke into major league baseball with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Ten years later, with his hall of fame career established, he retired. This is usually where the story of Jackie Robinson ends. Instead, I learned that his retirement years were often as interesting as his playing years. Robinson jumped into politics. He raised money for and marched with civil rights groups. He joined political campaigns and wrote a weekly newspaper column, not about sports but about politics and the Black experience. I learned that Robinson’s breaking of the color line in 1947 was just one instance of a lifetime of civil rights activism. And I realized that a course focusing on Jackie Robinson could contribute to Geneseo’s effort to become an antiracist campus.

Baseball as a prism

I titled the course Jackie Robinson, Baseball, and American Racism. I told my students that we would examine his life and times in order to better understand racism and antiracism in American history. “Although this course will focus mostly on Robinson as a baseball player,” I mentioned in the syllabus, “it will use baseball as a prism to engage with historical developments in the twentieth century, such as Jim Crow, the Cold War, the Civil Rights Movement, and the intersection of sports, politics, and culture.”

To my surprise, the course filled up quickly. Students seemed interested in a course on sports and also somewhat interested in Jackie Robinson. They were even more interested in an upper-level course during the intersession that met required elements for the History major. Nonetheless, they were game to join my experiment in offering a course on a topic that I had never taught previously or in such a condensed and online format.

I filled out the course with a long list of readings and assignments. I assigned five books, eighteen articles, and an array of other primary source documents. Students had to write daily discussion posts, a comparative film essay, a reflective essay, and a series of assignments leading up to a 15-page research paper. I was asking a lot from the students, but it was also a 400-level course. All of the reading and writing gave us the opportunity to have informed and stimulating synchronous discussions twice a week. The discussions built on extensive discussion posts in which students explored the creation of the color line in baseball, the extensive campaign among leftist groups and individuals to end segregation, Robinson’s persistent denunciations of racist policies and actions, and many other topics. We often connected the history with the present, noting how similar Robinson was, for example, to Colin Kaepernick.

For the research project, every student wrote about the struggle against racism. Most chose a sports figure. Some examined the ways that racism contributed to other forms of exclusion. This project gave students an opportunity to explore antiracism in their own way, and I think that they each gained valuable insight from it. On the other hand, it was very difficult to create an original research project in less than four weeks. Most students lamented the constraints they faced in locating online sources and finding time to research while keeping up with the other course expectations. Nevertheless, they all completed the research papers on time.

Is knowledge enough?

Overall, the course was a great experience. The students were engaged and worked hard. I missed having them in a classroom and I wish I could have gotten to know them better, but it was a successful online intersession course. During our last meeting, a few students suggested that I expand the course beyond Jackie Robinson and baseball if I were to teach it during a 16-week semester. I see the value in their critique. This course could be reconceptualized as one that engages racism in sports more broadly (in boxing and football, for instance) and one that addresses other barriers in sports, specifically gender and sexuality. Indeed, I learned that sports offer a discursive framework that might enable better discussions on inequities and inequalities. It is a prism, as I mentioned in the syllabus, to explore significant political and cultural issues.

More specifically, I have been reflecting on how my course did and did not engage with antiracism. On the one hand, the course could be considered antiracist because much of the content addressed historical efforts to mitigate racist policies. But is antiracist content enough? I’ve taught African American history for many years now, but I’ve never identified my courses as “antiracist.” All of my courses grapple with the history of racism and the effects of racist policies on people’s lives. So, why haven’t I called it this before?

During my Teaching and Learning Center presentation on my course, “Teaching Antiracism through Sports History and Jackie Robinson,” my colleague Crystal Simmons asked an interesting question. She wondered if I had noticed any shifts among my students in their beliefs or understandings about race or racism. I mentioned a few anecdotal interactions that somewhat answered the question. Reflecting on this question later, I realized that I didn’t really know if the course had changed a student’s understanding of racism partly because I didn’t set up the course that way. I didn’t include, for example, a learning outcome on antiracism. As is typical of 400-level History courses, I included our skills-focused learning outcomes, but I hadn’t considered what an antiracist objective would look like. And I’m still not sure what one would be. I think it would need to be more than just an acknowledgement that students will become aware of racism and antiracism. Knowledge is a good first step, but is it enough? In many ways, antiracism is a value, not a skill and not necessarily content. If antiracism is a value, how then do we construct learning outcomes that meet a set of values? Perhaps some of my colleagues in other disciplines have already tackled this issue. One thing this course has taught me is that I need to learn more about how to be more intentionally antiracist in course design, not just in content.